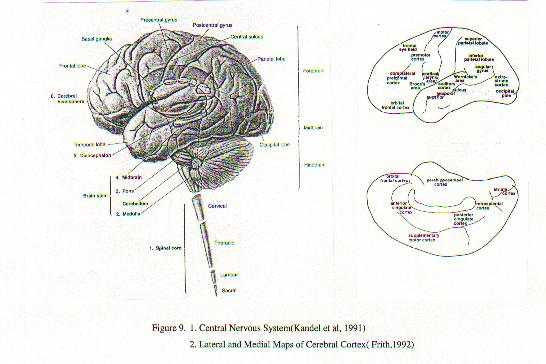

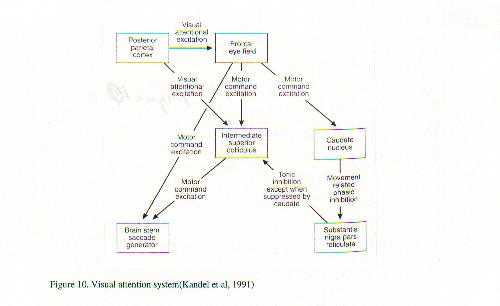

A neurobiological approach to the role of attention and automaticity was outlined by

Schneider et al(1994). This also emphasises the different processing areas in the brain

involved in effortful controlled processing and the automatic processing which have been

shown to be at the centre of the argument’s concerning the basis of schizophrenia.

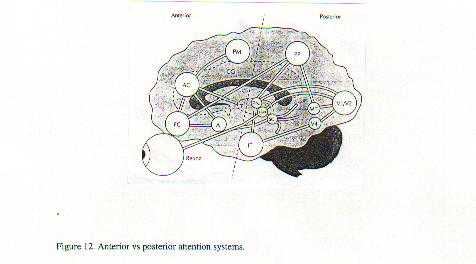

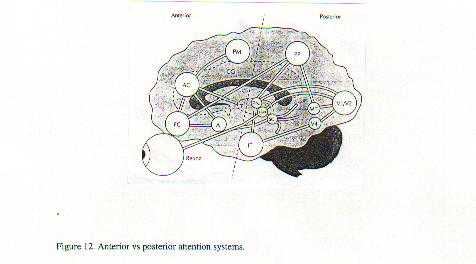

They also argue that the emphasis is on anterior prefrontal cortical activation in

deliberate controlled attention relative to posterior parietal functioning when tasks

become automatised. The functional areas are shown below in figure 12.

This resultant automatisation is explained as the resulting from posterior parietal

synaptic connections being strengthened or primed, as a result of task performance, in

acordance with Hebb’s synaptic strengthening rule. They note that in schizophrenia,

over time, processing continues to be maintained, predominantly, in the controlled mode.

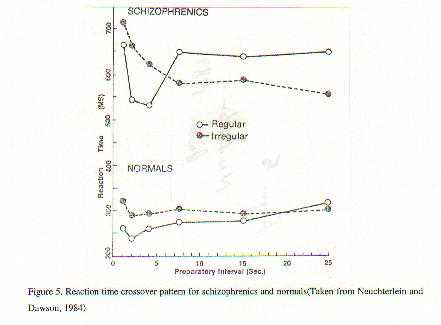

This factor, maintenance of controlled processing, would appear to be consistent with some

of the reaction time deficits found in schizophrenics’ attentional task performance.

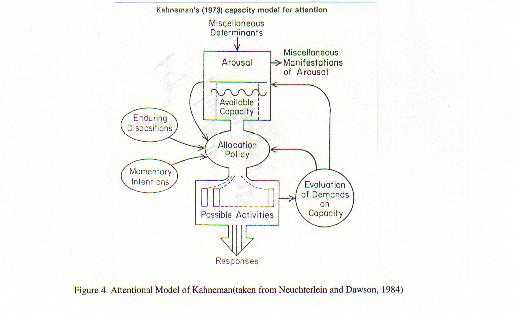

It has been shown that schizophrenics cannot modulate attention and they maintain

consistently high levels of arousal during selective attentional tasks(Frith et al,1988)

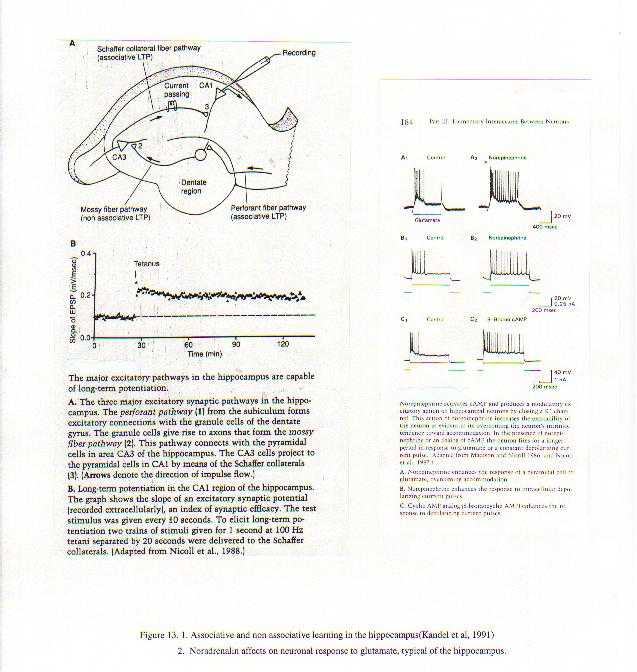

It has also been noted that functionality in the hippocampus increases with arousal but

when arousal reaches a critical level, hippocampal processing of information is reduced.

The earlier discussion, that had electrical stimulation of the temporal lobes causing

‘real’ experiences that did not occur in the other association areas, infers

that retrievable long term memories are stored in the temporal lobes. The role of the

hippocampus in storage of longterm memories has been demonstrated with amnesics, such as

HM, where bilateral hippocampal removal was carried out. They have lost the capacity to

encode retrievable memories for events that occurred after the damage but not for those

that occurred beforehand (Best, 1990, p189).

In terms of the priming which also results from automatic processing it is often

thought schizophrenics have excessive priming although many studies show that priming

levels are normal. It was suggested that priming might increase above normal when

neuroleptics were administered because this slowed down processing. Another interesting

possibility is the generator effect (Best, p159). When subjects are asked to generate a

word instead of just viewing it, their explicit memory in the form of recognition is

enhanced compared to priming effects. However when they do not generate words, but just

view them, priming effects are greater relative to recognition effects. If greater priming

does occur in schizophrenics as a result of a genetic characteristic it may well result in

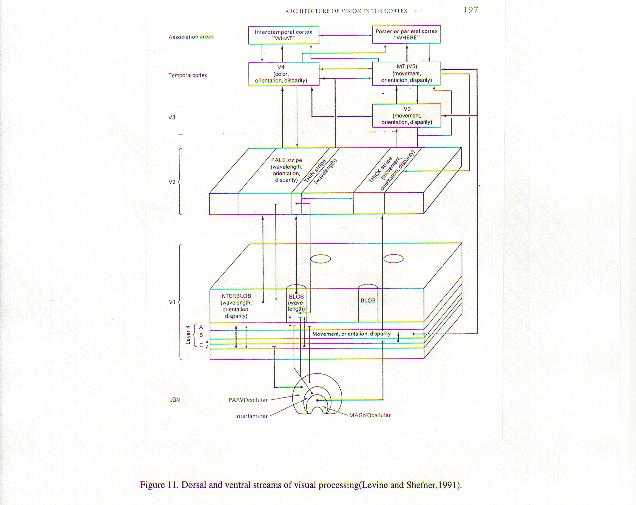

the continuous processing of information through the non automatic ventral stream. This

process would be closer to generation than automatic processing and could be used as a

means of diminishing priming effects. This decrease in priming would create social

perceptions closer to that of normals but at the cost of the cognitive exhaustion that

would result from continuous controlled processing.

Another distinguishing feature of schizophrenia is the age of onset, typically around

the age of 20 in males and a little later in females. Is this consistent with the above

theory regarding an emphasis on controlled processing? One area of anatomical abnormality

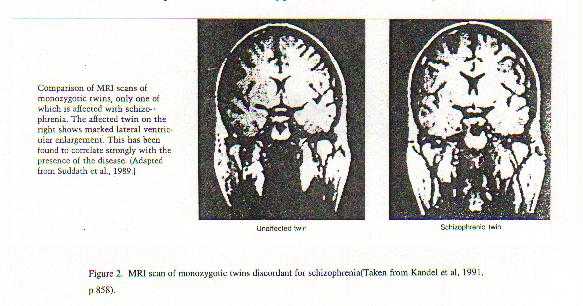

that is often found in schizophrenics is decrease in size of the hippocampus(Bogerts et

al,1985). It would seem that, as discussed, the hippocampus is involved in controlled

processing or at least involved in encoding the information used in controlled processing,

longterm memories. It has been noted on a number of occasions that schizophrenics show

elevated arousal levels and that this causes increased excitability of hippocampal

neurons(Zahn, 1985). Myelination of the hippocampus is not completed until the late

twenties(Bencs et al, 1994) and the onset of increased retrievable longterm processing may

well be the cause of psychological problems which result in an over emphasis on controlled

processing resulting in a pathological outcome. This could be the result of vaso

constriction which seems to be associated with hippocampal activation(Sergent,1994).

Metcalfe et al, (1996) notes that the memories related to hippocampal processing are

‘cool’ memories devoid of emotional contamination but automatic processing,

which also involves the amygda, results in emotional memories or ‘hot’ memories

that can be repressed by the frontal lobes in conjunction with hippocampal memories but

this takes effort. This is a biological framework for repression. This appears to be

exactly what is happening in schizophrenia except that it is totality of automatic

processing outcome that is being suppressed rather than a specific incident.

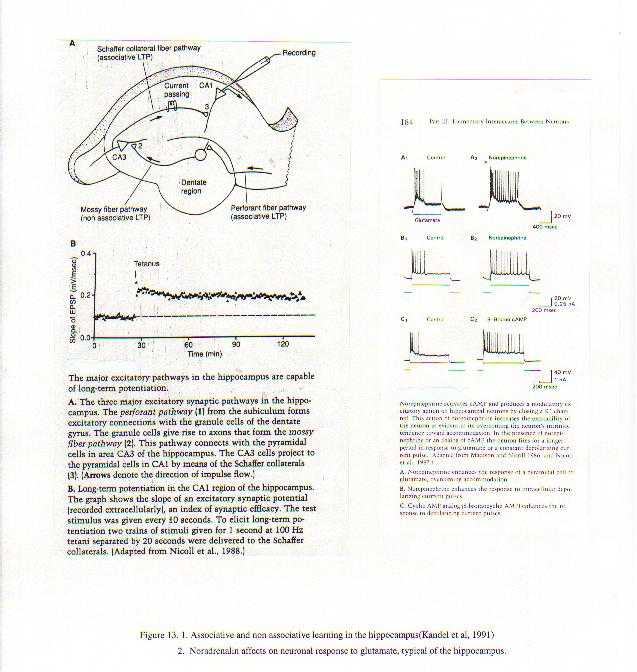

The genetic predisposition causes high natural arousal levels which activate the

hippocampus resulting in unusual controlled processing outcomes such as greater

associative learning, as well as a less fluent interaction with the posterior parietal

system of automatic processing (see figure 13). This would create the peculiarities

observed in schizotypal personality such as difficulties in social context, magical

thinking etc. but they still maintain their psychological integrity because they do not

try to suppress this abnormality.

CONCLUSION

Given that thought disorder has been shown to have no genetic basis it

would seem that the onset of pathology in schizophrenia is therefore the result of faulty

strategies to cope with either developmental factors or social factors facilitated by high

arousal levels or other genetic influences resulting in increased neural excitability such

as abnormal glutamate receptor expression (Akbaran et al,1995). As arousal levels increase,

emotional salience and emotional memories, encoded into the automatic system via the

amygdala, create further psychological pressure to ‘flee’ into the controlled

mode of processing.

Attempts to ‘generate’ memories or safer realities through the organizational

capacities of the prefrontal cortex result in ‘hallucinations’ and

‘delusions’ with a detached over activation of ‘inforamtion’ encoded

in the temporal cortex ie positive symptoms. The delusions come from the higher levels of

valid spatial and temporal associations that would occur as a result of heightened

hippocampal function. It is the interpretation of these associations, especially the

erroneous attribution of causality that lead to delusions although it works both ways in

that often valid associations in regard to social interaction are denied by others ie

there have often been clinical reports where patients say even their own relatives say one

thing when they mean another. The distractibility that occurs on attentional tasks would

be generated by this focus on internal stimuli.

Negative symptoms result from a downregulation of arousal and this may result from a

learned vaso constriction capacity, which often happens after traumatic evnts, and a

passive interaction with the ventral stream of processing. This may eventually result in

cortical atrophy in the parietal areas(Zahn,1985). The lack of activation of prefrontal

areas then allows a slower more deliberate approach to task performance.

This would explain the schizophrenic dependence on concrete, object centred cognition

as opposed to the automatic, abstract and socially relevant processing that occurs in the

automatic processing mode that is associated with the dorsal posterior parietal lobe. Van

den Bosch(1994) quotes a number of patients who talk about cognitive fragmentation.

This tends to indicate that the binding capacity of the parietal cortex is playing a

secondary role to the object perception in the temporal lobe.

If the noradrenergic fibres that activated the parietal lobe neurons did so via the b -adrenergic receptors, which are widely distributed in parietal and

prefrontal cortex, we would have a situation that enabled faster performance once focus

had returned to the posterior parietal system. This would be consistent with the faster

disengagement of attention noted in schizophrenics but the slower activation of this

system results from the constant engagement of the ventral of processing. This results in

deficits in reality monitoring, central monitoring of action and social contextual

judgements, all of which rely on automatic processing.

This biological view is consistent with the attentional data presented and the

anatomical data on atrophy does not indicate irretrievable damage from cell death and

probably results from vaso constricion either self induced as a slowing mechanism or

resulting from uncontrolled excesses of noradrenalin. Acute treatment with drugs should

only be short term. A cognitive-behavioural therapy approach which explains the faulty

interactions with others as well as activities which stimulate the posterior parietal

cortex and nutritional support would seem to be the desired approach. However it may well

be that a continuum in terms of the genetic effects means that arousal level is so high

that hippocampal activity and processing will create extreme examples and this seems to be

the case with autistics.

A final note in that an interesting comparison has emerged between the schizophrenic

and the psychopath. While both have poor frontal lobe performance at certain stages, the

schizophrenic appears to be deficient in automatic processing(parietal lobe) and the

psychopath in controlled processing(temporal lobe). The schizophrenic places spiritual and

mystical interpretations on events, has a pathological lack of self awareness and a lack

of social ‘grace’. The psychopath is just the opposite and is regarded as

materialistic, selfish and socially adroit and manipulative.

REFERENCES

Akbaran, S., James, K., Potkin, S., Hagman, J., Taffazoli, A., Buney, W. and Jones,

E.(1995) Gene Expression for Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase is Reduced Without Loss of

Neurons in Prefrontal Cortex of Schizophrenics. Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol

52, 258-266.

Bencs, F., Turtle, M., Khan, Y., and Farol, P.(1994) .Myelination Of Hippocampal

Area Sharply Increases From Childhood To Adolescence To Adulthood. Archives Of General

Psychiatry, (51) 477-484.

Best,J.(1992) Cognitive Psychology 3rd Edition. West Publishing, New

York.

Bogerts, B., Meertz, E. and Schonfeldt-Bausch, R(1985). Basal Ganglia and Limbic

System Pathology in Schizophrenia: A Morphometric Study of Brain Volume and Shrinkage.

Archives of General Psychiatry, August 42(8), 784-791.

Bosch, R van den, Rombouts, R and Asma, M van(1996). What Determines Continuous

Performance Task Performance. Schizophrenia Bulletin, Vol 22, No 4.

Cai, Z. (1990). The neural mechanism of declarative memory consolidation and

retrieval: A hypothesis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews, 14(3) 295-304.

Cannon,T, Zorrilla, L, Shtasel, D, Gur,R, Gur,R, Marco, E, Moberg,P And Price,

A.(1994). Neuropsychological Functioning In Siblings Discordant For Schizophrenia And

Healthy Volunteers. Archives Of General Psychiatry, 51:651-661

Collinge, J and Curtis, D.(1991) Decreased Hippocampal Expression of Glutamate

Receptor Gene in Schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. Vol 159, 857-859

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders(DSM IV)1994. The American

Psychiatric Association. Washington USA.

Elkins.I And Cromwell, R(1994). Priming Effects In Schizophrenia: Associative

Interference And Facilitation As A Function Of Visual Context. Journal Of Abnormal

Psychology, Vol 103, No 4,793-800.

Finkelstein, J, Cannon, T, Gur, R, Gur, R, And Moberg, P.(1997). Attentional

Dysfunctions In Neuroleptic-Na´ve Neuroleptic Withdrawn Schizophrenic Patients And Their

Siblings. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology, Vol 106, No2 203-212.

Frith, C., Stylem, M., Johnstone, E. and Crow, T.(1988). Acute Schizophrenic

Patients Fail to Modulate Their Level of Attention. Journal of Psychophysiology, vol

2(3), 195-200.

Frith, C.(1992). The Cognitive Psychology of Schizophrenia. Erlbaum Press, UK.

Gold, J, Randolp, C, Carpenter, C, Goldberg,T And Weinberger, D. (1992)Forms Of

Memory Failure In Schizophrenia. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology, Vol101 No 3 487-494.

Goodale, Melvyn A. And Milner, A. David. Separate Visual Pathways For Perception And

Action. Trends In Neuroscience, Vol 15, No1, 1992.

Gorenstein, E.(1982). Frontal Lobe Function in Psychopaths. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, Vol 91 No 5, 368-379.

Gras-Vincendon, A., Manion, J., Cramge,D., Bilik, M. and Willard-Schroeder, D., Sichel,

J. and Singer, L.(1994). Explicit Memory, Repetition Priming and Cognitive Skill

Learning in Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, Vol 13, 117-126.

Gur R And Gur R.(1995) Hypofrontality In Schizophrenia:RIP. Lancet Vol 345

1383-1384.

Kandel, E., Schwartz, J. and Jessel, T.(1991). Principles of Neural Science 3rd

Edition, Appleton and Lange, NY.

Kay,S.(1990) Significance of the Positive-Negative Distinction in Schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia Bulletin, Vol 16(1), 635-652.

Levine, M. and Shefner, J.(1991)Fundamentals of Sensation and Perception 2nd

Edition. Brooks/Cole Publishing, USA.

Liotti, M, Dazzi, S And Umilta, C(1993). Deficits Of The Automatic Orienting Of

Attention In Schizophrenic Patients. Journal Of Psychiatric Research, Vol 27 No 1,

119-130.

Mesulam, M. (1990). Large Scale Neurocognitive Networks and Distributed Processing

for Attention, Language and Memory. Annals of Neurology Vol 28 No 5.

McGuffin, P and Murray, R(1991). The New Genetics of Mental Illness. Oxford:Butterworth-Heineman,

London.

Mirsky, A, Yardley,S, Jones,B, Walsh, D, And Kendler,K(1995) Analysis Of The

Attention Deficit In Schizophrenia: A Study Of Patients And Their Relatives In Ireland.

Journal Of Psychiatric Research Vol29, No1. 23-42.

Mlakar, J Jensterle J And Frith, C.(1994) Central Monitoring Deficiency And

Schizophrenic Symptoms. Psychological Medicine 24, 557-564.

Nestor, P, Faux, S, Mc Carley, R, Penhume, V, Shenton,M, And Pollak, S.(1992) Attentional

Cues In Chronic Schizophrenia: Abnormal Disengagement Of Attention. Journal Of

Abnormal Psychology, Vol 101, No4 682-689.

Posner, M And Petersen, S.(1990)The Attention System Of The Human Brain. Annual

Review Of Neuroscience, 3:25-42.

Posner, M, Early,T,Reiman,E, Pardo,P and Dwaman, M.(1988)Asymmetries in hemispheric

control of attention in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry,45, 814-821.

Raine, A and Venables, P.(1988) Enhanced P3 Evoked Potentials and Longer P3 Recovery

Times in Psychopaths.Psychophysiology, Jan 25(1) 20-38.

Raz, S.(1993) Structural Cerebral Pathology in Schizophrenia: Regional or Diffuse.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, August Vol 102(3), 441-452.

Saykin, A J, Gur, R Gur, R, Mosely P, Mozely,L, Resnick, S Kester, B and

Stafiniak, P. (1991) Neuropsychological Function in Schizophrenia: Selective

Impairment In Memory And Learning. Archives Of General Psychiatry, Vol 48 July.

Schmand, B, Kuipers, T, van der, Gaag, M, Bosveld, J, Bulthuis, F and Jellema,M.(1994) Cognitive

Disorders and Negative Symptoms As Correlates Of Motivational Deficits In Psychotic

Patients. Psychological Medicine,24, 869-884.

Schneider W Pimm-Smith, M, Worden,M.(1994) Neurobiology of Attention and

Automaticity. Current Opinion In Neurobiology, 4:177-182.

Schroeder, Sichel,Jean Paul And Singer, Leonard.(1994) Explicit Memory, Repetition

Priming And Cognitive Skill Learning In Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, Vol 13,

117-126.

Schwartz,F, Munich,R, Carr, A, Bartuch, E, Lesser, B, Rescigno, D And Viegner, B. Negative

Symptoms And Reaction Time In Schizophrenia. Journal Of Psychiatric Research, Vol 25

No 3,131-140.

Sacuzzo, D., and Schubert, D.(1981) Backward Masking as a Measure of Slow Processing

in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology Vol 90 No 4,

305-312.

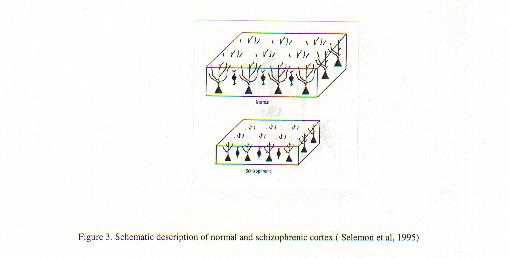

Selemon, L., Rajkowska, G and Goldman-Rakic, P.(1995). Analysis of Prefrontal Area

and Occipital Area 17. Archives of General Psychiatry, October Vol 52(10), 805-818.

Sergent, J.(1994). Brain-Imaging Studies of Cognitive Functions. TINS, vol 12

No.6.

Strauss, E, Novakovic, T, Tien,A, Bylsma,F And Pearlson, G.(1991). Disengagement Of

Attention In Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 37:139-146.

Taylor, S, Kornblum, S And Tandon, R(1996) Facilitation And Interference of

Selective Attention In Schizophrenia. Journal Of Psychiatric Research, Vol 30 No 4,

251-259.

Van den Bosch, R.(1994). Context And Cognition In Schizophrenia. Published In

"Advances in the Neurobiology of Schizophrenia". (Eds) Boer, J. den,

Westernberg, H. and Praag, H.. Chicester, Wiley.

Venables, P. and Patterson, T.(1978). Speech Perception and Decision Processes in

Relation to Skin Conductance and Pupillographic measures in Schizophrenia. Journal of

Psychiatric Research vol 14(1-4),183-190.

Ward, P, Catts, S, Fox, A, Michie, P, And Mcconaghy,N.(1991). Auditory Selective

Attention And Event Related Potentials In Schizophrenia. British Journal Of

Psychiatry, 158, 534-539.

Zahn T (1985) Studies of Autonomic Psychophysiology and Attention in Schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia Bulletin 14(2) 265-268.